Scaffold degradation is a key factor in cultivated meat production. It must align with tissue growth: too fast, and cells lose support; too slow, and tissue development is disrupted. Bioreactors, especially with dynamic flow, accelerate degradation compared to static setups, releasing acidic byproducts and altering scaffold structure. Accurate measurement ensures consistency and quality in scaling production.

Key Insights:

- Material Selection: Blends like PCL (slow degradation) and PLGA (faster degradation) allow customisation.

- Bioreactor Setup: Dynamic flow (e.g., 4 mL/min) mimics physiological conditions but speeds up hydrolysis.

-

Measurement Methods:

- Weight loss (gravimetric analysis).

- Structural changes (SEM imaging).

- Molecular weight tracking (GPC).

- Real-time pH monitoring and cyclic voltammetry for permeability.

Combining techniques provides a detailed understanding of degradation, helping optimise scaffold design and bioreactor conditions for reliable cultivated meat production.

Preparing Scaffolds and Setting Up the Bioreactor

To achieve accurate degradation measurements, it's crucial to establish precise baseline conditions and properly configure the bioreactor. Inadequate preparation can lead to issues like uneven moisture levels and sterilisation errors, which can distort degradation results. These initial steps are the foundation for reliable analysis.

Choosing Scaffold Materials

Selecting the right scaffold material is key, as the degradation rate must align with the rate of tissue formation. Biomaterials research suggests that "The ideal in vivo degradation rate may be similar or slightly less than the rate of tissue formation" [3]. For cultivated meat, this means using materials that hold their structure long enough for cells to develop their extracellular matrix, while eventually breaking down to allow tissue maturation.

Blending polymers can help fine-tune these properties. For instance, Poly(ε‑caprolactone) (PCL) is known for its durability and slow degradation, while Poly(D,L‑lactic‑co‑glycolic acid) (PLGA) degrades more quickly but offers less structural support [1]. In March 2022, researchers at the University of Zaragoza used 3D printing to create cylindrical scaffolds (7 mm diameter, 2 mm height) from a 50:50 mix of PCL and PLGA. Testing these scaffolds in a customised perfusion bioreactor with a flow rate of 4 mL/min, they observed that dynamic flow conditions significantly sped up hydrolysis compared to static setups over a four-week period [1].

Hydrophobic scaffolds, such as those made from synthetic polyesters like PLGA, resist water penetration, which can limit the culture medium's access to internal pores. To address this, pre-wet hydrophobic scaffolds in ethanol to ensure complete buffer penetration [3]. Additionally, the composition of PLGA - specifically the ratio of lactic acid to glycolic acid - directly impacts its degradation rate, with higher glycolic acid content leading to faster breakdown [1].

| Material Property | Poly(ε‑caprolactone) (PCL) | Poly(D,L‑lactic‑co‑glycolic acid) (PLGA) |

|---|---|---|

| Degradation Rate | Slow [1] | Fast (adjustable via LA/GA ratio) [1] |

| Mechanical Resistance | High [1] | Low [1] |

| Common Use | Long-term support [1] | Rapid tissue remodelling/drug delivery [1] |

Once the scaffold material is chosen, the next step is configuring the bioreactor to mimic physiological conditions for effective monitoring of degradation.

Configuring the Bioreactor for Degradation Studies

Setting up the bioreactor to replicate physiological conditions ensures consistent and reproducible measurements. Maintain a temperature of 37°C and an atmosphere of 5% CO₂ with 21% O₂ [1][5]. Whether to use static or flow perfusion environments is a critical decision - flow conditions not only accelerate hydrolysis but also introduce shear stress, better simulating in vivo environments [1].

For uniform testing, use individual closed-circuit chambers. The University of Zaragoza team, for example, used a system with four separate chambers connected by Tygon tubing, with a roller pump maintaining a PBS flow rate of 4 mL/min [1]. This setup allowed them to test multiple scaffold formulations while controlling environmental variables.

Careful medium management is essential. Replace the medium every 48 hours to prevent acidification caused by degradation byproducts [1]. Monitor pH levels during these replacements, as a drop in pH can indicate the release of acidic compounds like lactic or glycolic acid, providing an early sign of scaffold breakdown [1].

To ensure accurate baselines, follow these pre-treatment steps:

- Weigh scaffolds using a microbalance with 1 µg precision to record their initial mass [1].

- Sterilise all bioreactor components, including tubing and chambers, by autoclaving at 120°C for 45 minutes [1].

- Sterilise scaffolds with UV irradiation instead of autoclaving, as high temperatures can prematurely degrade thermoplastic materials [1].

- Pre-wet hydrophobic scaffolds in ethanol before placing them in the bioreactor [3].

- After experiments, rinse scaffolds at least twice (5 minutes each) in deionised water to remove residual salts from PBS [1][4].

- Use lyophilisation (freeze-drying) to achieve a constant weight before taking final measurements [1][4].

For researchers working on cultivated meat, sourcing high-quality bioreactor components and scaffold materials is easier through platforms like Cellbase, a B2B marketplace connecting professionals with trusted suppliers.

Methods for Measuring Scaffold Degradation

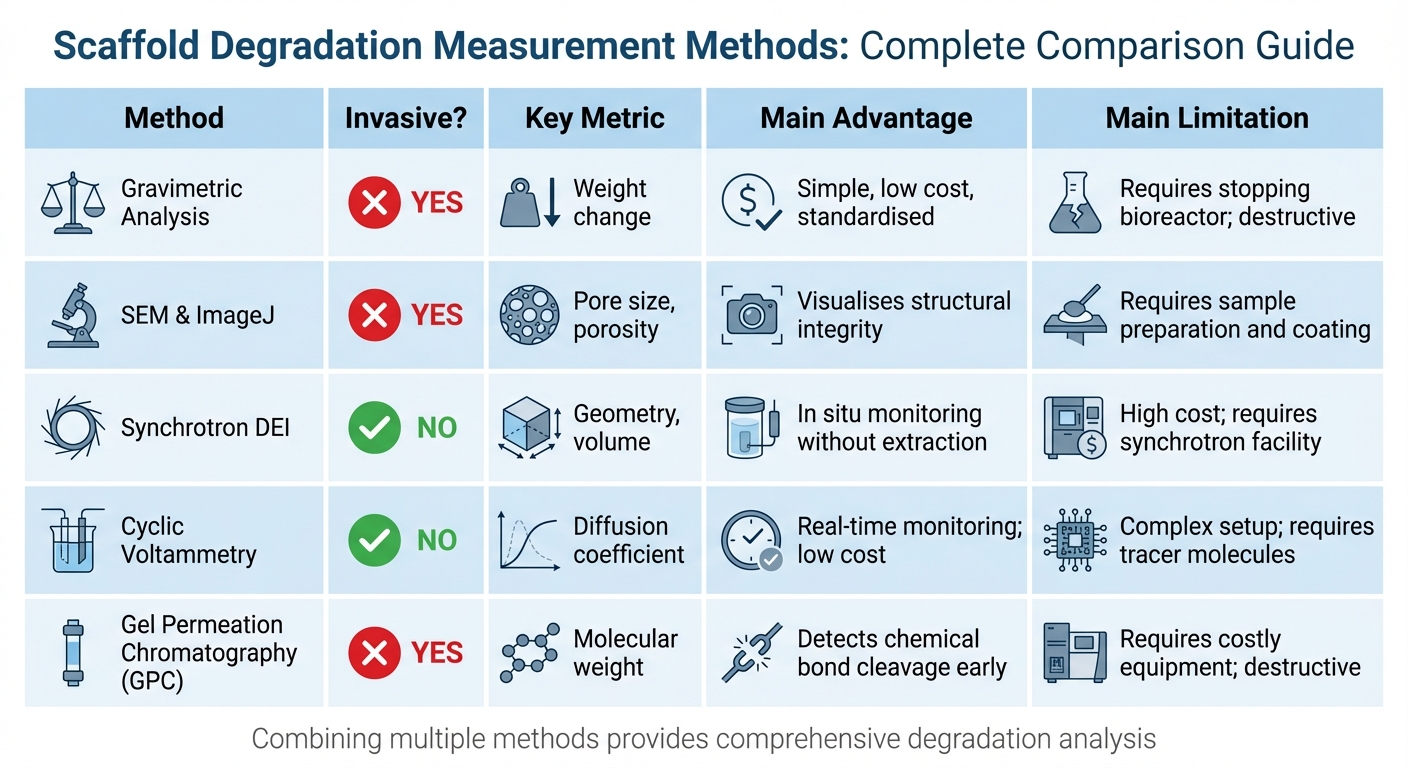

Comparison of Scaffold Degradation Measurement Methods for Bioreactors

After setting up your bioreactor and preparing the scaffolds, choosing the right measurement techniques is crucial. Each method offers unique insights into how scaffolds degrade, from tracking weight loss to analysing structural changes. Combining multiple methods can give a more complete picture, which is essential for improving cultivated meat production.

Mass Loss and Weight Change Analysis

Gravimetric analysis is a straightforward way to monitor scaffold degradation, often used alongside imaging and electrochemical methods. The process involves weighing the scaffold at the start using a microbalance with 1 µg precision, incubating it at 37°C in the bioreactor, and then re-weighing it at specific intervals. The percentage of mass loss is calculated using this formula:

WL(%) = (W₁ – W_f) / W₁ × 100

Here, W₁ is the initial dry weight, and W_f is the final dry weight[1].

For accurate results, follow the established preparation protocol. ASTM F1635-11 guidelines recommend a precision level of 0.1% of the total sample weight[5]. Additionally, the degradation medium should be replaced every 48 hours, and pH levels should be monitored during these exchanges to detect early signs of degradation[1].

In March 2022, researchers at the University of Zaragoza studied PCL-PLGA scaffolds in a perfusion bioreactor with a flow rate of 4 mL/min. Over four weeks, they found that while static conditions caused minimal changes after two weeks, dynamic flow significantly accelerated mass loss. By the end of the study, pH levels had dropped to about 6.33[1].

Imaging Techniques for Structural Changes

Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) is ideal for detecting micro-level changes in scaffold structure that weight measurements can’t reveal. It provides detailed images of surface quality, pore size, and emerging defects during degradation[1]. For reliable data, analyse at least 30 pores per sample using ImageJ software[1].

Preparing SEM samples involves drying them with ethanol gradients, lyophilisation, and applying a conductive carbon coat[1]. Using this method, researchers at the University of Zaragoza observed pore size changes in PCL-PLGA scaffolds. Initially under 1 µm, pore sizes increased to 4–10 µm after four weeks under dynamic flow conditions[1].

For continuous monitoring, synchrotron-based Diffraction-Enhanced Imaging (DEI) is a powerful tool. It allows researchers to track degradation without removing scaffolds from the bioreactor. In July 2016, a team at the University of Saskatchewan used DEI at the Canadian Light Source to study PLGA and PCL scaffolds. By measuring strand diameter changes in planar images at 40 keV, they estimated volume and mass loss over 54 hours in an accelerated NaOH degradation medium, achieving results within 9% of traditional weighing methods[6].

While imaging provides detailed structural information, non-invasive techniques offer the advantage of real-time monitoring.

Non-Invasive Monitoring Techniques

Real-time pH monitoring is a simple, non-invasive way to detect early scaffold degradation. By integrating pH sensors into the bioreactor’s perfusion loop, you can track medium acidification without halting operations[1].

Cyclic voltammetry is another non-invasive method that measures scaffold permeability. This electrochemical approach tracks the diffusion of tracer molecules, such as potassium ferrocyanide, through the scaffold. For example, in a study of collagen/glycosaminoglycan scaffolds, the effective diffusion coefficient for ferrocyanide decreased from 4.4 × 10⁻⁶ cm²/s to 1.2 × 10⁻⁶ cm²/s after degradation at 37°C[2]. This technique is cost-effective and suitable for quick evaluations, though it requires a more complex setup[2].

| Method | Invasive? | Key Metric | Main Advantage | Main Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gravimetric Analysis | Yes | Weight change | Simple, low cost, standardised[1][5] | Requires stopping the bioreactor; destructive[5] |

| SEM & ImageJ | Yes | Pore size, porosity | Visualises structural integrity[1] | Requires sample preparation and coating[1] |

| Synchrotron DEI | No | Geometry, volume | In situ monitoring without extraction[6] | High cost; requires a synchrotron facility[6] |

| Cyclic Voltammetry | No | Diffusion coefficient | Real-time monitoring; low cost[2] | Complex setup; requires tracer molecules[2] |

How Bioreactor Conditions Affect Scaffold Degradation

Measuring scaffold degradation accurately is essential, especially in cultivated meat production, where scaffolds must break down at a pace that supports tissue growth without disrupting cell development. The conditions inside a bioreactor - whether static or dynamic - play a major role in determining how scaffolds degrade. Static systems and dynamic flow environments can lead to very different degradation rates and patterns, which makes understanding these processes crucial for optimising bioreactor performance [1][3].

Dynamic vs Static Bioreactor Environments

The environment within a bioreactor - static or dynamic - directly influences how scaffolds degrade. In static systems, acidic byproducts can accumulate, triggering autocatalysis. This process speeds up internal polymer degradation and lowers the pH of the surrounding environment [8].

Dynamic systems, on the other hand, introduce fluid movement, which creates shear stress and improves mass transfer. These factors significantly affect degradation, depending on the scaffold material. For example, PCL-PLGA scaffolds experience faster hydrolysis under dynamic flow conditions (4 mL/min) compared to static systems. Over four weeks, this difference leads to distinct pore structures, offering valuable insights for bioreactor optimisation [1].

"Flow perfusion is critical in the degradation process of PCL-PLGA based scaffolds implying an accelerated hydrolysis compared to the ones studied under static conditions."

– Pilar Alamán-Díez, University of Zaragoza [1]

Interestingly, PLA-PGA scaffolds, which have low porosity, behave differently. A gentle flow rate of 250 µl/min helps flush out acidic byproducts, reducing the degradation rate before autocatalysis can take hold [8]. These contrasting effects highlight the importance of tailoring bioreactor protocols to the specific scaffold composition.

| Condition | Pore Size (4 Weeks) | Degradation Pattern | pH Stability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Static | 3–8 µm | Accelerated due to acid build-up | Significant local acidification |

| Dynamic (Flow) | 4–10 µm | Faster in PCL-PLGA; slower in PLA-PGA | Byproducts removed; pH stabilised |

Using Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD)

To further understand the effects of static and dynamic conditions, computational fluid dynamics (CFD) models are used to predict how fluid flow impacts scaffold degradation. These models simulate the interaction of fluid movement, mass transport, and the chemical reactions involved in polyester hydrolysis [7]. By applying reaction-diffusion equations, CFD can track water penetration, monitor ester bond concentrations, and map the movement of pH-altering byproducts within the scaffold.

CFD offers a unique advantage: it reveals how shear stress is distributed across the scaffold. In cultivated meat production, excessive shear stress can weaken the scaffold before tissue formation is complete [8]. By modelling both laminar and turbulent flow fields, researchers can identify optimal flow rates that balance nutrient delivery with scaffold preservation. For instance, CFD analysis has shown how a flow rate of 250 µl/min can effectively remove acidic byproducts, influencing the degradation kinetics of PLA-PGA scaffolds [8].

As scaffolds degrade, their geometry changes, which must be accounted for in CFD models. Effective diffusion coefficients are adjusted as porosity increases [7]. Additionally, incorporating molecular weight thresholds - approximately 15,000 Daltons for PLGA and 5,000 Daltons for PCL - ensures the model captures when polymer chains become soluble and begin to diffuse out, leading to measurable mass loss [7]. To speed up calibration, researchers often use thermally accelerated ageing (55°C to 90°C) and apply Arrhenius extrapolation to predict scaffold behaviour at physiological temperatures (37°C) [9]. These findings are instrumental in refining bioreactor protocols for cultivated meat production.

sbb-itb-ffee270

Combining Degradation Metrics for Complete Analysis

Relying on just one method to measure scaffold degradation often leaves critical gaps in understanding. By combining multiple techniques, researchers can build a fuller picture that captures both internal changes and structural effects [1][3]. This comprehensive approach is crucial in cultivated meat production, where scaffolds need to degrade at a precise pace - fast enough to support tissue growth, but not so quickly that structural integrity is lost before cells deposit sufficient extracellular matrix [1][3].

Degradation typically unfolds in three key stages: the quasi-stable stage (where molecular weight decreases but the scaffold remains visibly intact), the decrease-of-strength stage (marked by a decline in mechanical properties), and the final stage of mass loss or disruption (when visible degradation occurs) [3]. To monitor these stages effectively, physical (e.g., mass loss), chemical (e.g., molecular weight, pH changes), and structural (e.g., porosity, imaging) metrics are combined [1][5]. This multi-faceted approach helps differentiate between simple material dissolution and actual chemical degradation, which is vital for optimising bioreactor conditions. These stages also tie directly into the evaluation methods discussed later.

Comparing Degradation Metrics Across Methods

Each technique for measuring scaffold degradation brings unique advantages but also has limitations. For example, gravimetric analysis (weighing scaffolds) is simple and affordable, but it can't distinguish between a scaffold dissolving physically and one undergoing chemical breakdown [5]. Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC), on the other hand, can detect early degradation by tracking molecular weight changes, but it requires specialised equipment and destroys the sample in the process [1][5]. Similarly, Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) offers detailed visualisation of pore structures but often alters samples during preparation [1][5].

Here’s a quick comparison of key metrics and their respective techniques:

| Metric | Measurement Technique | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mass Loss | Gravimetric Analysis | Simple, low-cost, widely used [5] | Can't differentiate dissolution from chemical degradation; requires drying [5] |

| Structural Changes | SEM / Micro-CT | Detailed visualisation of pore sizes and connectivity [1] | Often destructive (SEM); expensive and time-intensive [7][1] |

| Mechanical Properties | Compression Testing | Measures functional integrity, important for load-bearing scaffolds [1][3] | High variability; destructive; requires specific sample shapes [3] |

| Molecular Weight | GPC / SEC | Detects chemical bond cleavage early, even before mass loss [1][5] | Requires costly equipment and dissolving samples in solvents [1][5] |

| Permeability | Cyclic Voltammetry | Non-invasive, real-time monitoring of pore connectivity [2] | Indirect; requires tracer molecules and complex data analysis [2] |

A study at the University of Zaragoza demonstrated the power of this integrated approach by using customised perfusion bioreactors to analyse PCL-PLGA scaffolds. They combined weight loss, GPC, SEM, and X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) to track degradation comprehensively [1].

Applying Results to Cultivated Meat Production

The insights gained from this integrated degradation analysis directly inform scaffold design and bioreactor management for cultivated meat. For success, the scaffold’s degradation rate must align closely with the rate of tissue formation [3]. If the scaffold breaks down too quickly, it loses structural support before enough extracellular matrix forms. Conversely, if it degrades too slowly, the final product may suffer from an undesirable texture or mouthfeel [3][1].

One practical solution is blending polymers. For instance, mixing fast-degrading materials like PLGA with slower-degrading ones like PCL allows researchers to fine-tune degradation rates to match specific cell types and growth timelines [1]. Continuous pH monitoring also helps, as acidic byproducts from degradation signal active breakdown [1]. Additionally, non-invasive techniques like cyclic voltammetry allow for real-time adjustments in bioreactor settings without interrupting the culture process [2].

For those involved in cultivated meat research, platforms like Cellbase offer a valuable resource for sourcing bioreactors, scaffolds, and analytical tools tailored to cellular agriculture needs.

Conclusion

Accurately measuring scaffold degradation is a cornerstone of cultivated meat production. It ensures scaffolds break down at the right pace - providing essential support during early tissue growth while allowing proper development as cells deposit their extracellular matrix. Striking this balance is crucial to maintaining structural integrity and ensuring successful tissue maturation.

Using a combination of measurement techniques offers a detailed understanding of scaffold degradation in dynamic bioreactors. Physical methods like tracking mass loss, chemical analyses such as Gel Permeation Chromatography to monitor molecular weight changes, and structural imaging tools like Scanning Electron Microscopy work together to distinguish between structural breakdown and the chemical degradation of materials. This data is essential for fine-tuning both bioreactor conditions and scaffold composition to optimise production [1][5].

Such insights play a pivotal role in developing polymer blends and making real-time adjustments during production. By ensuring that scaffolds support early cell growth and degrade as the extracellular matrix matures, these techniques enable the production of high-quality, scalable cultivated meat. For researchers and production teams, platforms like Cellbase provide access to verified suppliers of bioreactors, scaffolds, and analytical tools tailored to the specialised needs of cultivated meat production.

FAQs

How does the scaffold material affect its degradation rate in a bioreactor?

The rate at which a scaffold degrades in a bioreactor is heavily influenced by its chemical structure, crystallinity, and water absorption properties. Take poly(lactide-co-glycolide) (PLGA), for example - it degrades relatively quickly because it is hydrolytically labile. In contrast, polycaprolactone (PCL), which is more crystalline and hydrophobic, breaks down at a much slower pace.

These characteristics determine how the scaffold material reacts within the bioreactor, affecting processes like hydrolysis and erosion. Selecting an appropriate scaffold material is essential to ensure it retains its structure throughout the cultivated meat production process.

Why are dynamic flow conditions preferred over static conditions in bioreactors?

Dynamic flow conditions bring a host of benefits to bioreactor cultures compared to static setups. They improve the even distribution of nutrients, oxygen, and growth factors, creating a more consistent environment for cells to thrive. This leads to better cell survival rates and more efficient seeding processes than what static conditions can achieve.

On top of that, dynamic systems closely replicate physiological conditions, encouraging cells to behave more naturally and integrate effectively with scaffolds. These qualities are especially important in areas like cultivated meat production, where fine-tuning cell growth and scaffold functionality is essential.

Why is it necessary to use multiple methods to measure scaffold degradation?

Using several measurement techniques is crucial because no single method can fully capture all the details of scaffold degradation. Each approach targets specific aspects, such as mass loss, structural changes, or mechanical strength, and combining these methods gives a broader and clearer picture of the degradation process.

Relying on multiple methods also helps reduce the risk of errors or biases tied to any single technique, leading to more dependable results. This becomes especially important in intricate settings like bioreactors, where the performance of scaffolds plays a critical role in cultivated meat production.