Scaling bioreactors for cultivated meat production is complex, especially when managing shear stress, a mechanical force that can damage mammalian cells during scale-up. Unlike microbial cells, mammalian cells are fragile and sensitive to turbulence and aeration forces. When shear stress exceeds 3 Pa, cells can rupture, reducing viability and productivity.

To address these challenges, engineers rely on Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) and scale-down models to predict and manage shear stress before full-scale production. CFD analyses flow patterns, shear zones, and mixing efficiency in bioreactors, while scale-down models validate these predictions experimentally, minimising risks during scale-up.

Key Takeaways:

- Shear Stress Limits: Mammalian cells tolerate up to 3 Pa; exceeding this damages cells.

- CFD Tools: Advanced methods like Large Eddy Simulations (LES) and Lattice-Boltzmann simulations (LB-LES) enable precise modelling of flow and turbulence.

- Scale-Down Models: These replicate large bioreactor conditions in smaller setups to validate CFD predictions.

-

Design Considerations:

- Use pitched-blade impellers for lower shear.

- Maintain Kolmogorov eddy lengths above 20 μm to prevent cell damage.

- Keep impeller tip speeds below 1.5 m/s.

By combining CFD insights with experimental validation, teams can optimise bioreactor designs for cultivated meat production, ensuring cell survival and efficient scaling.

CFD Compass | Best Practices for Bioreactor CFD

Using Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) to Model Shear Stress

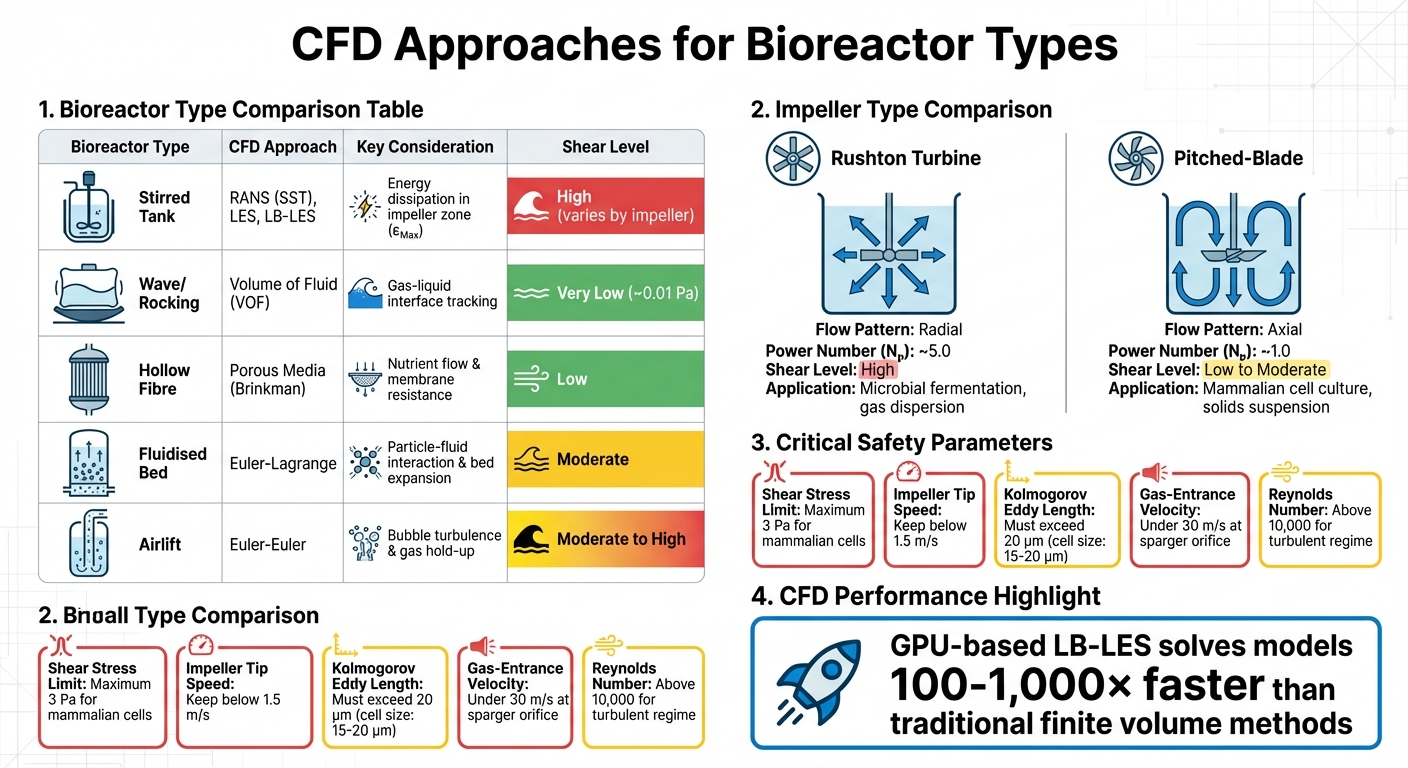

CFD Approaches and Key Parameters for Different Bioreactor Types in Cultivated Meat Production

CFD simulations give engineers the tools to map fluid dynamics and shear forces within bioreactors before they’re physically built. Instead of relying on trial-and-error methods at production scale, CFD helps predict critical factors like high-shear zones, turbulent eddies, and cell viability in specific parts of the vessel. This is especially important in cultivated meat production, where bioreactor scales could eventually reach 200,000 litres - far larger than traditional biopharmaceutical vessels [8]. These predictive insights guide scale-down experiments and influence equipment selection.

The evolution of computational techniques has been remarkable. While Reynolds-Averaged Navier-Stokes (RANS) models, such as k-ε, remain widely used in industry, advanced methods like Large Eddy Simulations (LES) and GPU-powered Lattice-Boltzmann simulations (LB-LES) are pushing boundaries. According to Professor Miroslav Soos from the University of Chemistry and Technology Prague, GPU-based LB-LES can solve models “100 to 1,000 times faster than commonly used finite volume method solvers” [2]. This speed advantage allows engineers to simulate massive vessels with the precision needed to detect cell-damaging eddies.

A practical example of CFD’s capabilities comes from researchers at Regeneron Ireland DAC and Thermo Fisher Scientific. They successfully scaled a cell culture process from a 2,000-litre bioreactor to a geometrically different 5,000-litre single-use bioreactor. Instead of relying on empirical heuristics, they used CFD to analyse parameters like mass transfer rates, mixing times, and shear rates. This approach enabled a successful scale-up on the first attempt, avoiding the costly failures often associated with power-per-volume ratio-based scaling [5].

Setting Up CFD for Stirred Tank Bioreactors

To set up CFD for stirred tank bioreactors, start by defining the vessel geometry - this includes tank dimensions, impeller design (e.g., Rushton or pitched-blade), and baffle placement. Choosing the right turbulence model is crucial: the realizable k-ε model works well for gas-liquid systems, while LB-LES offers higher resolution for identifying peak stresses that could harm cells. A grid convergence study ensures that results are not dependent on mesh size.

Boundary conditions must reflect real-world operating parameters, such as impeller speed, gas sparging rates, fluid density, and viscosity. For cultivated meat applications, conservative bubble drag models are often used to estimate shear stress [8]. The system should operate in a fully turbulent regime, with Reynolds numbers exceeding 10,000 to ensure that the power number remains consistent regardless of impeller speed [1].

CFD predictions for oxygen transfer, mixing times, and hydrodynamic stress should align with experimental data collected using shear-sensitive micro-probes or nanoparticle aggregates [2]. For instance, a mathematical mass-transfer model guided the direct scale-up of a CHO cell culture process from a 2-litre bench-top unit to a 1,500-litre industrial bioreactor at Sartorius. By using CFD to predict oxygen demand and CO₂ removal, the team maintained consistent product quality attributes - such as N-glycans and charge variants - across scales [6].

CFD for Other Bioreactor Types

While stirred tanks dominate industrial cell culture, other bioreactor designs require tailored CFD approaches. For example, rocking or wave bioreactors rely on the Volume of Fluid (VOF) method to simulate the gas-liquid interface, as wave motion drives shear stress in these systems. These designs create much gentler shear environments - maximum stress is about 0.01 Pa compared to stirred tanks - but their scalability is limited for large-scale cultivated meat production [4].

Hollow-fibre bioreactors, on the other hand, use porous media models based on Brinkman equations to simulate nutrient diffusion and flow resistance through membranes. Fluidised bed systems require Euler-Lagrange models to capture particle-fluid interactions and bed expansion, while airlift bioreactors use Euler-Euler methods to analyse bubble-induced turbulence and gas hold-up [4]. Each design comes with unique challenges: fluidised beds must balance microcarrier distribution against shear exposure, while airlift systems need to manage stresses caused by bursting bubbles, a leading cause of cell death in sparged bioreactors [1] [7].

Understanding these CFD approaches is essential for controlling shear stress across different bioreactor designs used in cultivated meat production.

| Bioreactor Type | CFD Approach | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Stirred Tank | RANS (SST), LES, LB-LES | Energy dissipation in the impeller zone (εMax) |

| Wave/Rocking | Volume of Fluid (VOF) | Tracking the gas-liquid interface |

| Hollow Fibre | Porous Media (Brinkman) | Nutrient flow and membrane resistance |

| Fluidised Bed | Euler-Lagrange | Interaction between particles and fluid, bed expansion |

| Airlift | Euler-Euler | Turbulence from bubbles and gas hold-up |

These varied CFD methods highlight the need for customised strategies, which play a critical role in equipment selection and shear stress management.

Scale-Down Models and Experimental Validation

While Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) provides valuable predictions, it cannot replace the need for real-world testing when scaling up processes. Experimental validation plays a crucial role in ensuring that computational models accurately represent real-world shear stress conditions. This is where scale-down models come into play, mimicking the hydrodynamic environment of large production bioreactors in smaller, easier-to-manage systems. By doing so, they reduce the risk of costly errors when moving from small-scale to industrial-scale operations. This step not only confirms CFD predictions but also ensures a more reliable and effective scale-up process.

Creating Scale-Down Models

Designing a scale-down model begins with maintaining geometric similarity. This means keeping the same aspect ratios between key components, such as the vessel height to diameter and the impeller diameter to tank diameter [11]. Once the geometry is aligned, engineers select a scaling criterion. Common choices include power per volume (P/V), impeller tip speed, or energy dissipation rate (EDR). However, focusing on localised EDR rather than average P/V provides a better understanding of shear heterogeneity, which is critical for accurate modelling.

A more advanced approach involves multi-compartment simulators. For instance, in February 2021, Emmanuel Anane and his team developed a two-compartment scale-down simulator combining a stirred tank reactor (STR) and a plug-flow reactor (PFR). This model was used to study how CHO cells respond to dissolved oxygen gradients. Their research revealed a critical residence time threshold of 90 seconds. Beyond this point, CHO cells showed a 15% drop in viable cell density and an increase in lactate accumulation [10]. This finding offers a clear benchmark for designing industrial bioreactors that maintain cell viability.

To safeguard cell growth, engineers often aim to keep impeller tip speeds below 1.5 m/s [1]. Additionally, the Kolmogorov microeddy length - a measure of turbulence - should exceed the size of the cells, typically 20 μm or more for mammalian cells, to avoid hydrodynamic damage [1][3]. For example, at an energy input of 0.1 W/kg in animal-cell cultures, the smallest eddies are around 60 μm, providing a safe buffer [3].

Validating CFD Predictions Through Experiments

Once a scale-down model is in place, experimental methods are essential for validating the parameters derived from CFD. Particle Image Velocimetry (PIV) is a widely used technique for this purpose. By tracking particles in the fluid, PIV helps confirm whether the flow patterns and velocity fields in the scale-down model align with CFD predictions [12][4].

Tracer injection and decolourisation methods are also used to validate mixing times. In this process, tracers like acids, bases, or salt solutions are introduced near the impeller, and their distribution is monitored until 95% homogeneity is achieved [12][3]. For large-scale mammalian cell bioreactors (5,000 L to 20,000 L), mixing times typically range from 80 to 180 seconds [10].

In March 2020, James Scully and his team at Regeneron Ireland DAC successfully scaled a cell culture process from a 2,000 L bioreactor to a 5,000 L single-use bioreactor with a different geometry. They relied on CFD to predict key parameters like mass transfer rates, mixing times, and shear rates. These predictions were then validated through single-phase and multiphase experiments, enabling a successful first attempt at scaling up without the need for large-scale pilot runs [5].

"CFD simulations are increasingly being used to complement classical process engineering investigations in the laboratory with spatially and temporally resolved results, or even replace them when laboratory investigations are not possible." - Stefan Seidel, School of Life Sciences, ZHAW [12]

Additional validation techniques include torque measurement to confirm specific power input (P/V) and dimensionless power numbers at specific stirrer speeds [12][3]. Oxygen transfer rates are verified using methods like the gassing-out or sulphite techniques, which determine the volumetric oxygen mass transfer coefficient (kLa) [12][7]. For systems using microcarriers, light attenuation or camera-based methods are employed to find the minimum speed needed to suspend all particles, ensuring that CFD predictions of solid phase distribution are accurate [12][4].

sbb-itb-ffee270

Factors That Affect Shear Stress in Bioreactors

To protect cell viability during scale-up, understanding the physical factors driving shear stress is critical. Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) predictions and scale-down validations reveal that energy dissipation rate (EDR) plays a key role. EDR measures how impeller kinetic energy converts to heat, leading to uneven energy distribution. For example, in pitched-blade impellers, energy tends to concentrate around the impeller, creating zones of high shear that can damage cells if not managed properly.

Impeller Design and Power Input

The type of impeller used significantly influences flow patterns and shear intensity. Rushton turbines, for instance, generate radial flow and high shear, making them ideal for microbial fermentation but less suitable for shear-sensitive mammalian cells. On the other hand, pitched-blade impellers create axial flow with lower shear and better pumping efficiency at the same power input. This makes them the preferred choice for applications like cultivated meat production, where cell viability is a priority.

| Impeller Type | Flow Pattern | Power Number (Nₚ) | Shear Level | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rushton Turbine | Radial | ~5.0 | High | Microbial fermentation; gas dispersion [3] |

| Pitched-Blade | Axial | ~1.0 | Low to Moderate | Mammalian cell culture; solids suspension [3] |

Scaling strategies often rely on maintaining a constant power input per volume (P/V). However, as reactor size increases, this can lead to higher impeller tip speeds. For mammalian cells, tip speeds should stay below 1.5 m/s to avoid growth issues [1]. In large-scale reactors, sparging can introduce even more hydrodynamic stress than impellers, especially in vessels exceeding 20 m³ [9]. These factors closely tie to turbulence, which is explored further in the Kolmogorov scale discussion.

Kolmogorov Scale and Turbulence Modelling

The Kolmogorov scale (λ) defines the size of the smallest turbulent eddies where energy dissipates as heat. If these eddies are smaller than the cell diameter, mechanical damage becomes a concern. For mammalian cells, which are typically 15–20 μm in size, the eddy length must exceed 20 μm to avoid damage [1][3]. For instance, at an energy input of 0.1 W/kg, the Kolmogorov eddy diameter is about 60 μm, providing a safe buffer [3].

"If biological entities (e.g., mammalian cells) are smaller than λ [Kolmogorov scale] in a bioreactor, then shear damage to such entities will not occur." - Muhammad Arshad Chaudhry [3]

In August 2024, researchers from Boehringer Ingelheim Pharma and the University of Chemistry and Technology Prague used Lattice-Boltzmann Large Eddy Simulations (LB-LES) to validate CFD predictions in a 12,500 L industrial bioreactor. By using shear-sensitive nanoparticle aggregates, they measured maximum hydrodynamic stress and demonstrated that LB-LES could resolve turbulent scales 100–1,000 times faster than traditional methods [2]. These findings are instrumental in developing strategies to minimise shear stress.

Reducing Shear Stress Using Modelling Data

CFD modelling enables engineers to pinpoint high-shear zones and adjust operating conditions accordingly. One effective approach is to introduce substrates, pH bases, or antifoams near the impeller zone rather than at the liquid surface. This ensures rapid distribution and minimises localised concentration gradients [3]. In cultivated meat production, excessive shear can detach cells from microcarriers, while insufficient agitation leads to microcarrier settling and nutrient imbalances [9].

Protective additives like Pluronic F-68 (Poloxamer 188) are commonly used to shield cells from shear forces, particularly those caused by bubble bursting at the liquid surface - a major contributor to cell death in bioreactors [1]. With these surfactants, energy inputs as high as 100,000 W/m³ have been reported without lethal effects [1]. Additionally, keeping the gas-entrance velocity at the sparger orifice under 30 m/s helps reduce productivity losses and cell mortality [1].

Finding Equipment for Bioreactor Scaling

How Cellbase Supports Bioreactor Procurement

Scaling up bioreactors for cultivated meat production comes with its own set of challenges. This is where Cellbase steps in. Unlike generic lab supply platforms, Cellbase is a specialised B2B marketplace tailored specifically for the cultivated meat industry. It connects researchers and production teams with trusted bioreactor suppliers, offering equipment that meets the unique demands of scaling cultivated meat production. One critical aspect addressed by Cellbase is managing shear stress - an issue that computational fluid dynamics (CFD) modelling reveals to vary significantly depending on reactor design and operating conditions. By aligning its listings with industry-driven CFD insights, Cellbase ensures that each piece of equipment meets strict standards for shear stress control.

When using Cellbase, procurement teams can evaluate bioreactors that have been tested against CFD predictions for maximum hydrodynamic stress (τmax) and mixing times. A case study from Regeneron Ireland DAC [5] highlights the importance of this approach. As Scully explained:

Successful scaling of the bioreactors used within the biopharmaceutical industry plays a large part in the quality and time to market of these products [5].

By leveraging CFD-backed data, teams can streamline equipment selection and minimise the need for repeated trial runs [5]. These insights are crucial for choosing bioreactors designed with optimal shear stress management in mind.

Choosing Equipment for Shear Stress Control

To control shear stress effectively, certain equipment specifications are particularly important. Impeller geometry is a key factor. For example, pitched-blade impellers generate axial flow with a power number (Np) of roughly 1.0, while Rushton turbines have a much higher Np of around 5.0. This means that pitched-blade designs produce significantly less power and, therefore, less shear at the same rotational speed [3]. For applications involving mammalian cells used in cultivated meat, keeping the impeller-tip velocity below 1.5 m/s is essential to avoid cell damage [1].

Sparger configuration is another critical consideration. To prevent excessive shear, equipment should ensure that gas-entrance velocity at the sparger orifice stays under 30 m/s, and the orifice Reynolds number remains below 2,000. Exceeding these thresholds can lead to the "jetting regime", where bubbles disperse unevenly and create localised shear zones [1]. Drilled-hole or open-pipe spargers are better suited for shear-sensitive cells compared to microspargers. Additionally, equipment should support scale-down compatibility. Suppliers offering bench-top models (e.g., 3 L systems) that are geometrically similar to large-scale systems (2,000 L or more) allow teams to validate CFD predictions on a smaller scale before moving to full-scale production [1][2].

Conclusion

Scaling bioreactors for cultivated meat production requires moving away from traditional trial-and-error methods and embracing model-driven strategies to address localised shear differences. Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) has become a key tool in this process, allowing engineers to predict hydrodynamic environments and visualise shear zones beyond simple power-per-volume ratios [1]. By adhering to critical parameters - like keeping Kolmogorov eddy lengths above 20 μm and impeller-tip speeds under 1.5 m/s - engineers can protect mammalian cells from shear damage while ensuring proper mixing and oxygen transfer [1].

Advanced computational methods, such as Large Eddy Simulation (LES) and Lattice-Boltzmann techniques, have shown their effectiveness in scaling up processes. For example, in March 2020, Regeneron Ireland DAC successfully scaled a cell culture process from a 2,000 L bioreactor to a geometrically distinct 5,000 L single-use system on the first attempt. This was achieved using multiparameter CFD predictions, eliminating the need for extensive physical trials [5]. This "first-time-right" strategy not only reduces contamination risks but also shortens the time to market - critical for the cultivated meat sector.

Experimental validation methods, such as Particle Image Velocimetry (PIV), further confirm the accuracy of CFD models [2]. These validated models now play a crucial role in procurement decisions. Companies like Cellbase are leveraging these insights to connect cultivated meat teams with suppliers offering equipment tailored for precise shear control. By aligning its marketplace with CFD-validated specifications, Cellbase helps researchers and production managers find systems that meet specific shear stress requirements, cutting down on the trial-and-error cycles that have historically slowed bioprocess scale-up.

FAQs

How does Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) support bioreactor scale-up for cultivated meat production?

Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) is a game-changer when it comes to scaling up bioreactors for cultivated meat. It provides a deep understanding of flow dynamics, shear stress, mixing efficiency, and mass transfer rates - all critical factors for creating the ideal environment for cell growth.

With CFD, engineers can optimise essential elements like impeller design, agitation speed, and gas sparging. This ensures that the bioreactors operate under the best possible conditions, safeguarding both cell health and productivity.

What’s more, CFD makes it possible to move from small laboratory setups to large industrial-scale bioreactors without compromising efficiency or consistency. This means cultivated meat production can scale up smoothly while maintaining high standards.

What makes Large Eddy Simulations (LES) better than traditional methods for bioreactor modelling?

Large Eddy Simulations (LES) provide a deeper and more precise look into turbulent flow within bioreactors compared to traditional methods like Reynolds-averaged Navier-Stokes (RANS). By focusing on large-scale eddies and modelling only the smallest dissipative motions, LES can pinpoint critical shear-stress hotspots, such as vortex-induced high-shear zones, that might otherwise be overlooked. This level of detail plays a key role in reducing cell damage and ensuring greater reliability when scaling up cultivated meat production.

Unlike methods that depend heavily on empirical correlations, LES offers stronger predictive capabilities when moving from lab-scale to industrial-scale bioreactors. Advances in computational techniques have also made LES more accessible, allowing for detailed simulations without the need for prohibitive computational resources. For businesses aiming to integrate LES-driven designs, Cellbase provides a trusted platform offering bioreactors, sensors, and specialised equipment tailored specifically to the complex requirements of cultivated meat production.

Why is it important to maintain Kolmogorov eddy lengths above 20 µm for mammalian cell viability?

Maintaining Kolmogorov eddy lengths above roughly 20 µm is crucial for safeguarding mammalian cells during bioreactor operations. When these turbulent eddies shrink below the size of the cells, they can expose the cells to excessive shear stress, which risks damaging their membranes and lowering cell viability.

Keeping the smallest turbulent structures larger than the cells helps reduce the chances of mechanical damage. This not only promotes healthier cell cultures but also enhances the overall performance of the bioreactor. This consideration becomes even more important during bioreactor scale-up, where ensuring consistent shear stress conditions is notably more difficult.