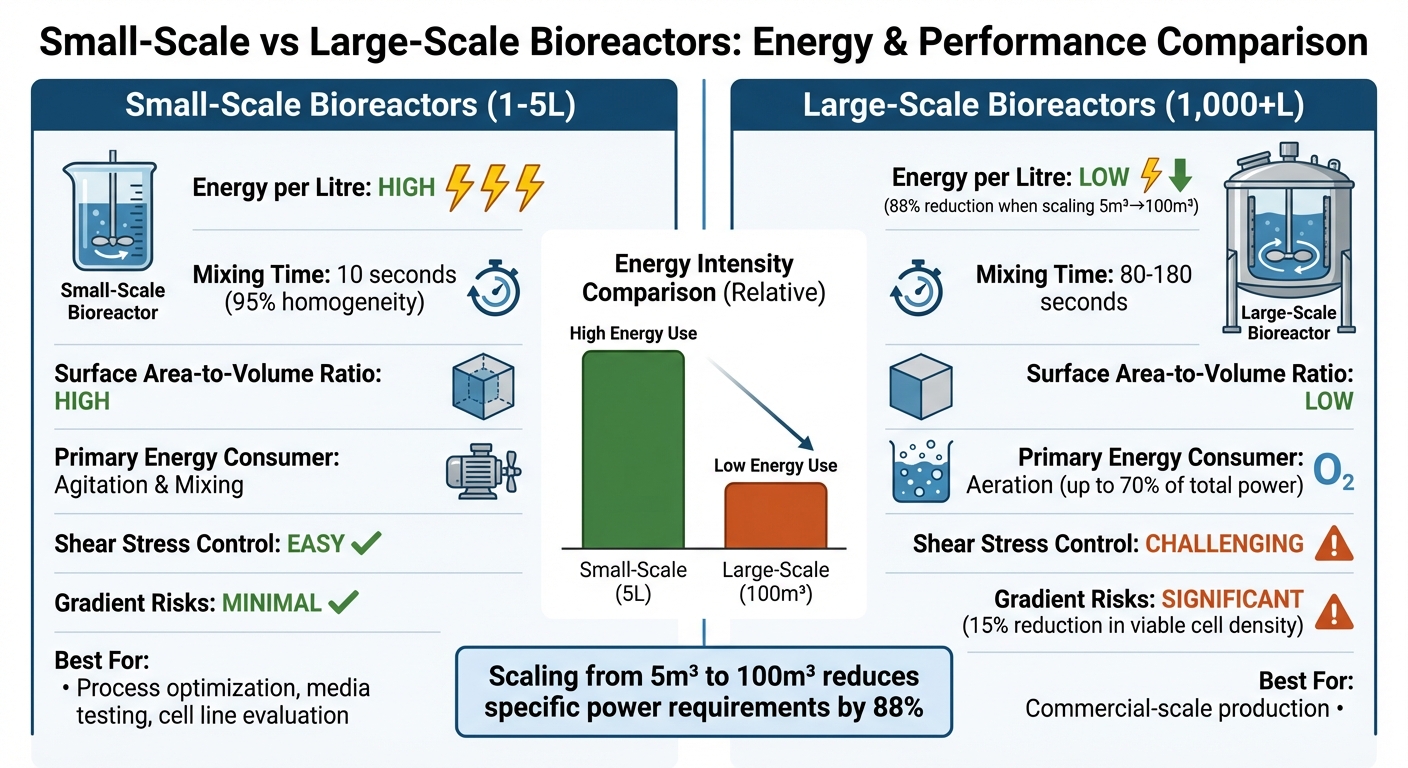

Scaling up bioreactors for cultivated meat production - from small (1–5 L) to large (1,000+ L) systems - brings energy challenges. Larger volumes require more power for mixing, oxygen transfer, and heat control, but they also offer efficiencies. For example, moving from 5 m³ to 100 m³ can reduce specific energy use by up to 88%. However, slower mixing in large systems can create oxygen and nutrient imbalances, affecting cell growth. Automated control systems and strategies like "flooding point" operation help balance energy use and maintain cell viability. Here's what you need to know:

- Small-scale bioreactors: High energy per litre, quick mixing, easier heat removal, but not ideal for large-scale production.

- Large-scale bioreactors: Lower energy per litre, slower mixing, more complex heat and gas management, but better for commercial production.

Energy efficiency improves with scale, but maintaining cell quality requires advanced automation and precise control of agitation, aeration, and temperature.

Fermentation Process Design and Scale-Up: Upstream Processing (USP)

sbb-itb-ffee270

1. Small-Scale Bioreactors (1–5 L)

Laboratory-scale bioreactors operate under very different energy conditions compared to their industrial counterparts. At this smaller scale, the performance of processes is generally influenced more by cell kinetics than by transport phenomena [2]. The high surface-area-to-volume ratio makes heat removal simpler, but it also means that agitation parameters can't be directly scaled up to larger systems. This dynamic often leads to agitation being the primary driver of energy consumption at this stage.

In small-scale systems, energy use is largely dictated by agitation and mixing. To achieve the same volumetric power input (P/V) as larger bioreactors, smaller ones need higher impeller speeds because of their smaller impeller diameters [2][9]. For mammalian cell cultures - key in cultivated meat production - a P/V of 20–40 W/m³ is typically optimal. This range supports cell growth while minimising cell aggregation [5].

Aeration adds another layer of complexity. The volumetric mass transfer coefficient (kLa) measures how efficiently oxygen reaches cells. However, increasing agitation to improve kLa can also raise hydromechanical shear stress. For shear-sensitive processes, like lentivirus production, open-pipe spargers are often preferred, as micro-spargers can reduce functional viral titres by as much as 25% [5]. Operating close to the flooding point, with lower agitation and higher aeration, can help balance energy use while meeting oxygen transfer needs [1].

Thermal management in these bioreactors is typically handled by water-based cooling systems, such as jackets or internal coils, to dissipate excess heat. Each watt of mechanical agitation generates heat that must be removed efficiently. Additionally, microbial metabolic activity produces around 14.7 kJ of heat per gram of oxygen consumed [7]. The refrigeration power required depends on the total heat generated and the cooling system's efficiency, with a typical coefficient of performance around 0.6. Adjusting agitator settings during different stages of a batch operation can significantly reduce energy consumption [7].

Modern small-scale bioreactors are equipped with automation systems that use sensors and algorithms to dynamically regulate pH, oxygen levels, and temperature. These systems ensure that only the necessary cooling or agitation is applied during each growth phase, reducing energy waste [6][10]. For cultivated meat companies sourcing equipment through platforms like Cellbase, choosing bioreactors with advanced automation features is essential. These tools not only optimise energy use but also provide accurate predictions for energy requirements, which is critical when planning the transition to larger-scale operations.

2. Large-Scale Bioreactors (1,000+ L)

When scaling up production, the challenges grow as mixing times increase significantly - from just 10 seconds in small 3-litre systems to a much longer 80–180 seconds in massive vessels ranging from 5,000 to 20,000 litres. These slower mixing times create operational hurdles, such as dissolved oxygen gradients and metabolic shifts, which can reduce viable cell density by up to 15% during the stationary phase [4]. For mammalian cell cultures used in cultivated meat production, crossing a 90-second mixing time threshold can trigger metabolic changes, leading to the accumulation of lactate [4]. To address these issues, adjustments to agitation and aeration strategies are essential at larger scales.

At these larger volumes, energy demands shift. Initially, agitation plays a bigger role in energy use when oxygen transfer rates are low. However, as cell growth accelerates, aeration becomes the dominant factor, accounting for as much as 70% of power consumption. Operating near the flooding point - a point where gas flow disrupts liquid mixing - remains critical, but at this scale, it’s primarily about managing the energy load from aeration. Increasing headspace pressure is another effective tactic, as it boosts oxygen solubility and reduces the need for high agitation speeds when oxygen transfer rates are high [9].

Thermal management also becomes more intricate at scale but offers opportunities for greater efficiency. For example, industrial fermentations show a wide range of power requirements: itaconic acid fermentation averages 0.51 kW/m³, while lysine production, which demands more oxygen, requires 2.61 kW/m³ [1]. Cooling systems typically achieve a refrigeration efficiency of around 0.6, though under ideal conditions, coefficients of performance can reach as high as 8.6 [7].

Scaling up from 5 m³ to 100 m³ can cut specific power requirements by as much as 88%, provided operations are optimised [9]. This is crucial for cultivated meat production, where balancing energy efficiency with maintaining product quality is key. Mechanistic modelling now enables production teams to forecast heat generation and power needs by combining microbial growth data with thermodynamic models [9][1]. For companies in the cultivated meat sector sourcing large-scale systems through platforms like Cellbase, selecting bioreactors equipped with advanced pressure control and automation features is vital to achieving these efficiency gains.

To fully capitalise on energy savings, optimised physical parameters must be paired with precise automation. Automation systems at this scale must juggle multiple demands effectively. One strategy involves segmenting the fermentation process into intervals where agitator power remains constant while airflow adjusts to match oxygen uptake, minimising energy use [7]. Modern control systems also monitor dissolved oxygen levels in real time, dynamically adjusting both mechanical and pneumatic settings to prevent the metabolic disruptions that occur when mixing times surpass physiological limits [4].

Advantages and Disadvantages

Small-Scale vs Large-Scale Bioreactor Energy Efficiency Comparison

Deciding between small- and large-scale bioreactors for producing cultivated meat involves weighing up energy efficiency, operational complexity, and suitability for production needs. Here's a closer look at how they compare:

| Feature | Small-Scale Bioreactors (1–5 L) | Large-Scale Bioreactors (1,000+ L) |

|---|---|---|

| Energy Intensity per Litre | High; requires more specific power to maintain uniformity and oxygen transfer [9][8] | Low; scaling from 5 m³ to 100 m³ can cut specific power needs by 88% [9] |

| Mixing Efficiency | Excellent; achieves 95% homogeneity in about 10 seconds [4] | Poor; takes 80–180 seconds, increasing the risk of gradients [4] |

| Surface Area-to-Volume Ratio | High; supports efficient heat removal and CO₂ stripping [2] | Low; poses challenges in managing heat and gas exchange [2] |

| Primary Energy Consumer | Agitation and mixing [9] | Aeration (up to 70% of total power during high cell growth) [9] |

| Shear Stress Management | Easier to control; cells are less exposed to damaging forces [3][4] | Harder to manage; high agitation can harm fragile animal cells [3][4] |

| Gradient-Related Risks | Minimal; rapid mixing avoids metabolic disruptions | Significant; oxygen gradients over 90 seconds can lower viable cell density by 15% [4] |

| Cultivated Meat Suitability | Ideal for optimising processes, testing media, and evaluating cell lines [3][8] | Critical for commercial-scale production; requires specialised low-shear designs [11][3] |

Benchtop bioreactors excel at achieving quick and uniform mixing, making them perfect for fine-tuning cell culture conditions. However, their high energy demands per litre make them less practical for large-scale production. On the other hand, large-scale bioreactors are far more energy-efficient on a per-litre basis, but they come with operational challenges that can affect cell viability. For instance, slower mixing times can create oxygen and nutrient gradients, which may disrupt the growth of shear-sensitive cells used in cultivated meat.

For companies working with suppliers like Cellbase, ensuring effective pressure control in bioreactor design is crucial for maintaining both efficiency and product quality. While large-scale systems can reduce specific power needs by as much as 88% [9], they must also meet the delicate biological conditions required for cell growth. These considerations highlight the balancing act between energy efficiency and biological performance, providing valuable insights for scaling up bioreactor operations.

Conclusion

Scaling up bioreactors offers a huge reduction in energy use per litre. For instance, moving from a 5 m³ to a 100 m³ bioreactor can slash specific power demand by 88% [9], making large-scale production far more cost-effective. However, this efficiency comes with a compromise. While smaller bioreactors achieve uniform mixing in about 10 seconds, larger industrial vessels take significantly longer - around 80 to 180 seconds. This slower mixing can create harmful dissolved oxygen gradients [4].

This shift in efficiency also changes where energy is consumed. In smaller systems, most of the energy goes into agitation. But at a commercial scale, especially with high cell densities, aeration becomes the dominant energy consumer, accounting for up to 70% of the total energy demand [9].

Automation is key to tackling these challenges. Tools like CAE, CFD, and AI allow producers to model and optimise the balance between agitation and aeration before scaling up physically [3]. Additionally, real-time sensors that monitor dissolved oxygen and carbon dioxide levels enable dynamic adjustments through automated control systems. These systems help prevent costly metabolic shifts, keeping energy use per kilogramme of product in check and paving the way for smarter scaling strategies.

For producers looking to expand, operating near the flooding point is often the most efficient approach. This strategy prioritises intense aeration over energy-heavy agitation [1]. Techniques like headspace pressurisation can further reduce the need for agitation during peak oxygen transfer [9]. When sourcing equipment, platforms such as Cellbase can help producers find bioreactors and control systems with advanced automation and sensor technology. These features maximise energy efficiency while maintaining the ideal conditions for cultivated meat production. Mechanistic modelling and cascade controls also play a vital role, helping to identify when agitation should give way to aeration, cutting waste without compromising cell growth [9].

FAQs

How does automation enhance energy efficiency in large-scale bioreactors?

Automation plays a crucial role in boosting energy efficiency in large-scale bioreactors by allowing for precise, real-time adjustments of critical parameters like agitation, aeration, temperature, and dissolved oxygen levels. Instead of sticking to rigid, overly cautious settings, automated systems rely on real-time sensor data to fine-tune these factors, ensuring energy is used efficiently to maintain the ideal conditions for cell growth.

This dynamic control is particularly beneficial during start-up and scale-up phases, where automation enables quick adjustments to changing process conditions, cutting down on unnecessary energy usage. By aligning control systems with the specific characteristics of bioreactor designs - such as stirred-tank or air-lift systems - automation not only improves consistency but also reduces the energy required to produce each kilogram of cultivated meat. These advancements are key to scaling up production efficiently while keeping the environmental impact in check.

What issues can arise from slower mixing times in large-scale bioreactors?

In large-scale bioreactors, slower mixing can cause uneven distribution of nutrients and oxygen, leading to the development of gradients. These gradients can disrupt cell growth, result in uneven waste accumulation, and reduce the system's overall efficiency.

To tackle these problems, operators often resort to higher power inputs. While this approach helps, it also drives up energy consumption and operating costs. Finding solutions to these challenges is essential to maintaining energy efficiency and achieving optimal performance during scale-up.

Why is operating close to the flooding point considered energy-efficient during bioreactor scale-up?

Operating close to the flooding point during bioreactor scale-up is often seen as an energy-efficient approach. This method optimises gas-liquid mixing, which is critical for effective mass transfer. By maximising the gas flow rate without pushing the system into instability, the bioreactor can function efficiently while keeping energy use in check.

That said, operating near this threshold requires careful monitoring and control. Pushing beyond the flooding point can disrupt the system or lead to a drop in performance, making precision a key factor in maintaining efficiency.